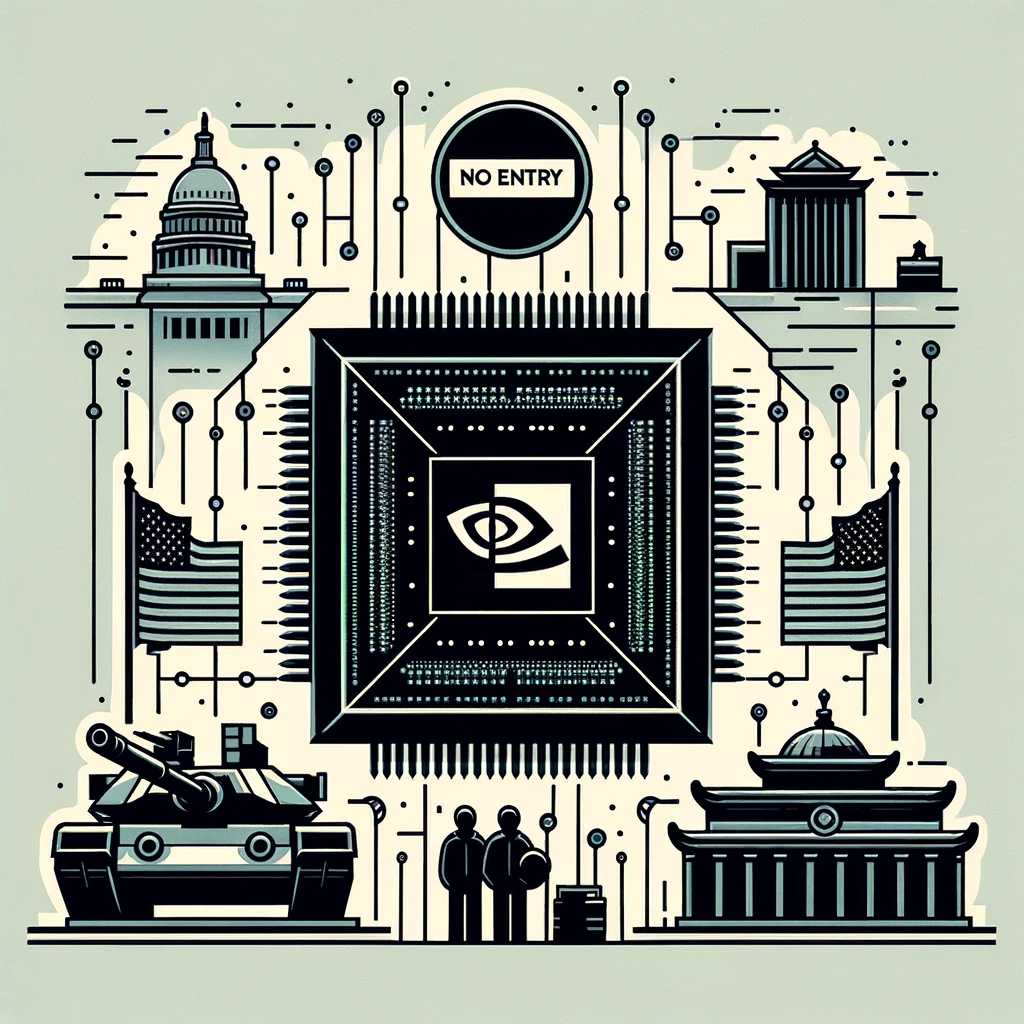

Over the past year, there has been a notable trend of Chinese military bodies, state-run artificial intelligence research institutes, and universities acquiring small batches of Nvidia semiconductors, despite U.S. export restrictions to China. This development, revealed through a Reuters review of tender documents, underscores the challenges faced by the U.S. in effectively severing China’s access to advanced U.S. chips. These chips are crucial in driving AI advancements and sophisticated computing capabilities for China’s military.

The sale of these high-end U.S. chips is not illegal in China. Publicly available tender documents indicate that dozens of Chinese entities have purchased and received Nvidia semiconductors since the imposition of export restrictions. These purchases include Nvidia’s A100 and the more advanced H100 chip, banned from export to China and Hong Kong in September 2022, and the subsequently developed, though slower, A800 and H800 chips, which were also banned in October 2022.

Nvidia’s graphic processing units (GPUs) are widely recognized for their superiority in AI work, as they efficiently process the massive amounts of data required for machine-learning tasks. Despite the burgeoning development of rival products from companies like Huawei, Nvidia had a dominant 90% share in China’s AI chip market prior to the bans. The continued demand and access to these banned Nvidia chips underscore the lack of viable alternatives for Chinese firms.

Among the purchasers are elite universities and entities like the Harbin Institute of Technology and the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, which are subject to U.S. export restrictions due to their alleged involvement in military activities or affiliations with military bodies. The Harbin Institute of Technology, for example, purchased six Nvidia A100 chips in May for training a deep-learning model, while the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China bought one A100 chip in December 2022 for an unspecified purpose.

None of the entities mentioned in the article responded to requests for comment. The Reuters review also found that neither Nvidia nor retailers approved by the company were among the suppliers identified in these transactions. The precise means by which these suppliers have procured Nvidia chips remain unclear.

However, an underground market for such chips in China has emerged in the wake of U.S. curbs. Chinese vendors have reportedly obtained excess stock from large shipments to U.S. firms or imported chips through companies in India, Taiwan, Singapore, and other locations.

Despite attempts to seek comments from ten of the suppliers listed in the tender documents, including those mentioned in the article, none responded. Nvidia, on its part, has stated compliance with all applicable export control laws and requires its customers to do the same. The company also mentioned taking immediate and appropriate action upon learning of any unlawful resale.

The U.S. Department of Commerce declined to comment, but U.S. authorities have expressed a commitment to closing loopholes in the export restrictions and limiting access to these chips by Chinese companies located outside of China.

Chris Miller, a professor at Tufts University and author of “Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology,” commented that it’s unrealistic to expect U.S. export restrictions to be completely foolproof, given the small size of chips and the ease with which they can be smuggled. The primary objective, according to Miller, is to hinder China’s AI development by making it challenging to build large clusters of advanced chips capable of training AI systems.

The Reuters review included over 100 tenders where state entities procured A100 chips, with dozens of tenders

since the October ban showing purchases of the A800. Tenders published last month indicate that Tsinghua University acquired two H100 chips, while a laboratory run by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology obtained one. Furthermore, an unnamed People’s Liberation Army entity in Wuxi, Jiangsu province, sought 3 A100 chips in October and one H100 chip recently.

Military tenders in China are typically heavily redacted, making it difficult to determine the winners of the bids or the exact purpose of the purchases. Most tenders indicate that the chips are used for AI, but the quantities purchased are relatively small, insufficient for building a sophisticated AI large language model from scratch. For instance, a model akin to OpenAI’s GPT would require over 30,000 Nvidia A100 cards, according to TrendForce. However, even a few chips can run complex machine-learning tasks and enhance existing AI models.

In one notable case, the Shandong Artificial Intelligence Institute awarded a contract worth 290,000 yuan (approximately $40,500) to Shandong Chengxiang Electronic Technology for 5 A100 chips. Many tenders stipulate that suppliers must deliver and install products before payment. Most universities also publish notices confirming the completion of transactions.

Tsinghua University, often compared to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the U.S., has been particularly active, purchasing around 80 A100 chips since the 2022 ban. In December, Chongqing University published a tender for an A100 chip, specifying that it must be brand new. The delivery was completed this month, as per a notice.

The procurement of these chips highlights the increasing challenges the U.S. faces in restricting China’s access to cutting-edge technology. Despite the bans, Chinese entities continue to find ways to acquire these crucial components, indicating the complexities and limitations of export controls in a globalized tech industry.

The significance of these purchases extends beyond mere acquisition; it reveals the strategic importance of semiconductors in the global technology race, particularly in areas like AI, where processing power and data handling capabilities are critical. The procurement of Nvidia chips by Chinese military and academic institutions reflects China’s ongoing efforts to advance its technological capabilities, particularly in AI and computing.

Moreover, these developments highlight the intricate and often clandestine nature of global semiconductor supply chains. While the U.S. seeks to curb China’s access to advanced technology, the ease with which these chips can be obtained through alternative channels poses a significant challenge. It underscores the need for more comprehensive and effective strategies to regulate the flow of critical technologies.

The situation also sheds light on the broader geopolitical tensions surrounding technology and trade between the U.S. and China. As the two countries vie for technological supremacy, the control and access to advanced semiconductors have become a key battleground. This is not just a matter of economic competition but also of national security and global technological leadership.

In response to these challenges, there is a growing emphasis on developing domestic capabilities in semiconductor technology. Both the U.S. and China have been investing heavily in their semiconductor industries, seeking to reduce reliance on foreign sources and enhance their technological sovereignty. This has led to

a surge in research and development efforts, as well as increased funding for semiconductor manufacturing and design.

The focus on domestic semiconductor production is not only about ensuring a steady supply of chips but also about maintaining a competitive edge in the global market. For China, this means reducing its dependence on U.S. technology, while for the U.S., it’s about safeguarding its technological leadership and preventing the transfer of sensitive technologies to potential adversaries.

The pursuit of semiconductor self-sufficiency is further driven by the realization that control over this technology is crucial for the future of numerous industries, including telecommunications, automotive, and healthcare. As AI continues to advance and find applications in various sectors, the demand for powerful and efficient chips like those produced by Nvidia will only grow.

The situation also raises questions about the effectiveness of export controls in the modern era. While such restrictions are intended to prevent the proliferation of sensitive technologies, the global nature of supply chains and the ease of transnational transactions make enforcement challenging. This is further complicated by the rapid pace of technological advancement, which often outstrips the ability of regulatory frameworks to keep up.

In light of these developments, there is a need for a more nuanced approach to technology export controls. This approach should consider the realities of global supply chains and the evolving nature of technology. It should also involve cooperation with international partners to ensure a coordinated and effective response to the challenges posed by the transfer of sensitive technologies.

The case of Chinese entities acquiring Nvidia chips despite U.S. bans is a clear indicator of the complex interplay between technology, economics, and geopolitics. It highlights the challenges in regulating the flow of critical technologies in a globalized world and underscores the strategic importance of semiconductors in the ongoing technological rivalry between the U.S. and China.

As the world continues to grapple with these issues, the semiconductor industry will remain at the forefront of geopolitical and economic discussions. The outcome of these debates will not only shape the future of the technology sector but also have far-reaching implications for global power dynamics and the future of international relations.

In conclusion, the procurement of banned Nvidia chips by Chinese military and academic institutions is a testament to the strategic significance of semiconductors and the challenges in controlling their global distribution. It highlights the need for more effective strategies to regulate critical technologies and underscores the ongoing technological competition between the U.S. and China. As the world moves forward, the semiconductor industry will continue to play a pivotal role in shaping the technological landscape and the geopolitical order.